How factories are deploying AI on production lines

By Liv McMahon & Alasdair Keane – Nov 16, 2023

A version of this article was first published on BBC

As Doritos, Walkers and Wotsits speed along a conveyor belt at Coventry’s PepsiCo factory – where some of the UK’s most popular crisps are made – the noise of whirring machinery is almost deafening.

But here, it’s not just human workers trying to hear signs of machine failure above the factory fray.

Sensors attached to equipment are also listening out for indications of hardware faults, having been trained to recognise sounds of weary machines that risk bringing production lines to a grinding halt.

PepsiCo is deploying these sensors, created by tech firm Augury and powered by artificial intelligence (AI), across its factories following a successful US trial.

The company is one of many exploring how AI can increase factory efficiency, reduce waste and get products onto shelves sooner.

Crunching the numbers

From early design to delivery, AI is seen as having a key role in a new wave of manufacturing.

Its ability to process and analyse huge volumes of data is already helping manufacturers predict and prepare for potential disruption.

A minute of factory downtime can cost companies thousands of pounds, and increased delays can mean missing out on consumer demand at critical moments like the festive period or Black Friday.

So tools that can check and analyse processes in real-time, warn of problems on the horizon, and harness historical data to recommend fixes are becoming familiar sights on factory floors.

The sensors used in PepsiCo factories have been trained on huge volumes of audio data, to be able to detect faults such as wearing on conveyor belts and bearings, while analysing machine vibrations.

“We have today over 300 million hours of machines that we’ve analysed and monitored, and we can leverage all this data to create algorithms that know how to pinpoint specific patterns of different malfunctions,” says Augury chief executive, Saar Yoskovitz.

By also collecting information and insights into equipment health on the whole, such as identifying when a machine might fail again in future, the technology lets workers schedule maintenance in advance, and avoid having to react to machine errors as they occur.

Using AI-powered sensors can also give the company a way to cut down on waste across its operations.

“If the machine is working in the most optimal way you can reduce the energy consumption of that machine”, says Mr Yoskovitz.

Computer vision, which involves training machines to recognise objects in images and video, is another type of AI being used across some of the world’s factories to detect product defects at-scale.

The flurry of items moving along conveyor belts and through sorting machines in factories mean miniscule defects in products can easily be missed.

This is particularly true of computer chip wafers and circuit boards that have intricate designs and components. Errors which might have previously gone unnoticed by the human eye can now be picked up by a machine’s camera, and caught by algorithms trained to spot specific, surface-level anomalies.

Improving visibility

Alexandra Brintrup, professor of digital manufacturing at the University of Cambridge’s Institute for Manufacturing, tells the BBC that the use of AI for improving efficiency in the industry, including in areas like predictive maintenance and quality control, can now be considered conventional applications of the technology.

“I feel like the more exciting opportunities of AI in manufacturing are going to come from things that we couldn’t even attempt to do before, like capacity sharing between manufacturers, improving visibility in supply chains, even sharing of trucks in a logistics chain,” she says.

The interwoven, complex nature of supply chain networks, and the reluctance of some stakeholders to say who supplies them, has previously kept many aspects of manufacturing shrouded in mystery.

But AI can be used to analyse and predict who and where suppliers are, giving companies an insight into bottlenecks, and consumers an insight into where their products are coming from, and the materials used.

Prof Brintrup leads the Institute for Manufacturing’s Supply Chain AI Lab, which has developed its own predictive mechanism to identify where ingredients such as palm oil may have been used in a product, but disguised under a different name on its label.

The lab’s recent research suggested that palm oil can go by 200 different names in the US – and these might not stand out to eco-conscious consumers.

“We have increasingly a society that is very much aware of the environmental and societal impact of manufacturing, so I think increased supply chain visibility and giving that information to the consumer is going to become more and more important,” Prof Brintrup adds.

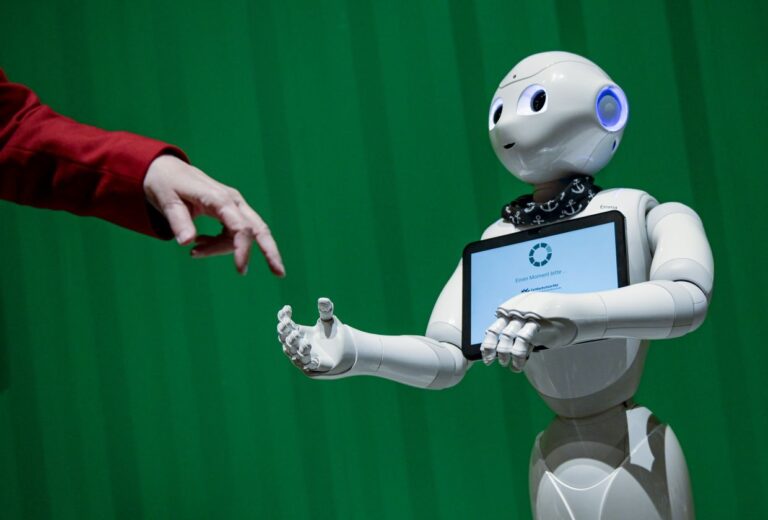

What about workers?

The question of what the rising adoption of AI tools on factory floors and in the wider supply chain will mean for workers looms large over the manufacturing landscape.

Some firms are exploring how AI can be used to keep production line workers safe around machinery – using machine learning and computer vision techniques to monitor factory camera feeds to identify possible threats or accidents.

Meanwhile, AI-powered wearables like exoskeletons have been deployed across UK warehouses to ensure people tasked with repeatedly carrying heavy loads aren’t getting strained or injured.

David Schwartz, global vice president of PepsiCo Labs, says that the firm sees Augury’s sensors and AI more broadly as a way to deliver more value for workers and customers, and not just to future-proof its factories.

“It’s helping enhance how people work, so we can bring better efficiency to meet the needs of our people, of our customers, and we can be prepared to lean into the future to meet their needs on a daily basis,” he says

Watch BBC Click to see how AI is being used to get snacks to shelves smoothly and also tackle wildfires.